6 When he saw Jesus from a distance, he ran and fell on his knees in front of him. 7 He shouted at the top of his voice, “What do you want with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? In God’s name don’t torture me!” 8 For Jesus had said to him, “Come out of this man, you impure spirit!” 9 Then Jesus asked him, “What is your name?” “My name is Legion,” he replied, “for we are many.” – Mark 5:6-9

Sermon delivered June 21, 2020

In the fifth chapter of Mark, we encounter Jesus as he enters the region of the Gerasenes and is approached by an unnamed man who had been forced to live among the tombs. This man, the text reads, is said to have an unclean spirit, no longer able to be bound or chained, and all night and day he would cry out from the mountains and cut himself with stones.

One way this text is understood is that the unnamed man was moved to live life among the tombs because he was the victim of an undisclosed spiritual issue. However, I would like to propose that this unnamed man living life in the tombs is, in fact, a victim of a much more sinister systemic issue that has driven him away from his community and rendered him essentially invisible from the rest of the world.

In Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, we are introduced to another unnamed man who narrates his own story and tells us of his experience as a black man caught in the discord of early-twentieth-century racism. Trapped living life in a sewer beneath the streets of a fictionalized Harlem, this self professed “invisible man” tells the reader that his invisibility is not the result of a physical condition, rather the result of others’ refusal to see him. Like the illusions cast by a skilled magician, he has been made invisible because when people approach him “they see only [his] surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”

I would like to propose that the Gospeller Mark, like Ellison, is telling us the story of an invisible man.

Mark is telling us a story of a man who is forced to live life trapped in an abyss. A man who has been victimized by community and ostracized by the world. An invisible man who has been stricken by the systemic social and racial realities that undergird the experiences of poverty, homelessness, and unemployment.

Like the protagonist in Ellison’s novel, this man has been rendered invisible because people do not chose to see him; instead what they see is a man living is life among the tombs – presuming him to be the victim of his own spiritual deprivation – rather than the product of a failed society that has pushed him, as well as far too many people like him, to live on the fringes and outskirts of society.

During my second year of graduate school, I was able to take my first trip out of the country to visit Cairo, Egypt as a part of a multicultural context course so that myself and my colleagues, living in a predominately Christian society, would get to experience life in predominately Muslim society.

One of the most striking memories I have from that trip was seeing off the highway a cemetery where many of the homeless in Cairo would live. This was not an uncommon reality people are faced with in this region of the world. But for many of us on this trip, seeing people living within a cemetery was a jarring and shocking experience because we could not fathom the degree of poverty that would force people to live their life among the tombs.

I would like to suggest that in even in this so-called Christian America, seeing people live among the tombs is not that much of an unfamiliar experience. Every day we drive by people who have been forced to make their home among the dead and dying, and who have been chained and trapped in certain parts of town that have been under-resourced and stripped of secure places to live.

Every day we see people who have been sequestered in food deserts – chained inside neighborhoods where there is over policing, lead in the water, and increased rates of murder and suicide. We interact with people every day who are striving as hard as they can to make ends meet as a result of the systemic policies that have turned once thriving and affluent communities into ghettos and cemeteries that are systemically prevented from ever thriving or being rebuilt again.

And I would like to argue that Mark’s story of this “invisible man” is a timely mirror to see the reflection of our own society that demonizes, dehumanizes, criminalizes, and systemically attacks countless amounts of people who have been alienated and violated by a system of racism and white supremacy leaving too many forced to live life among the tombs, particularly black men.

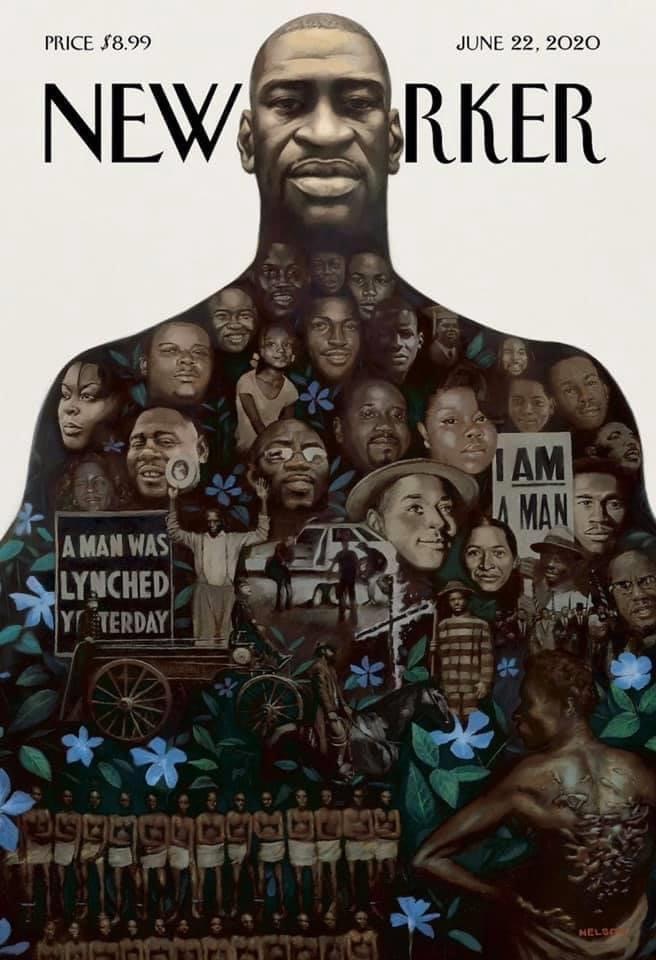

Over this past month we have lamented and grieved the death of George Floyd who’s daughter is now forced to spend this Father’s Day without her daddy.

We grieve the death of Philando Castile who was murdered in his car while his wife and daughter were with him in the vehicle.

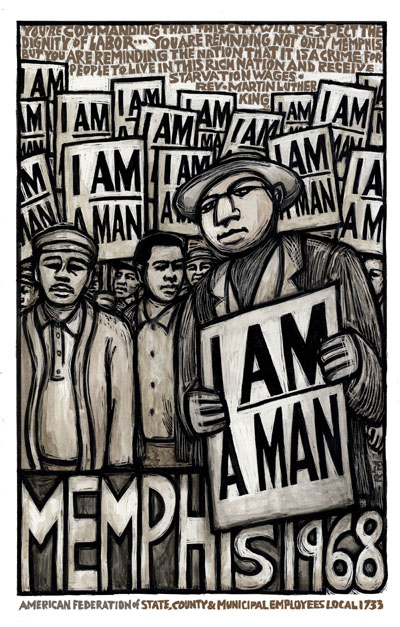

We lament the murders of Tamir Rice, Trayvon Martin, and Jonathan Edwards who was killed while shopping for gifts for his children. Black people have been trapped living life among the tombs because for too long we have had to bury too many of our people made victims of racism and anti-blackness inflicted against our flesh.

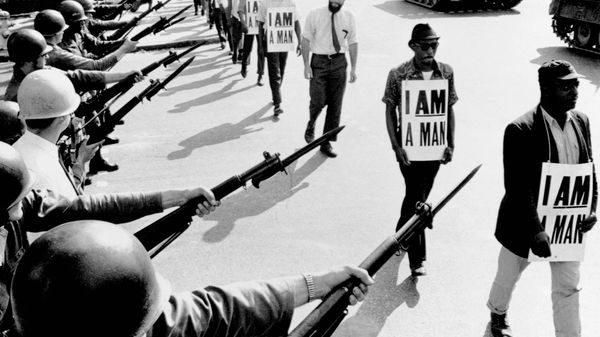

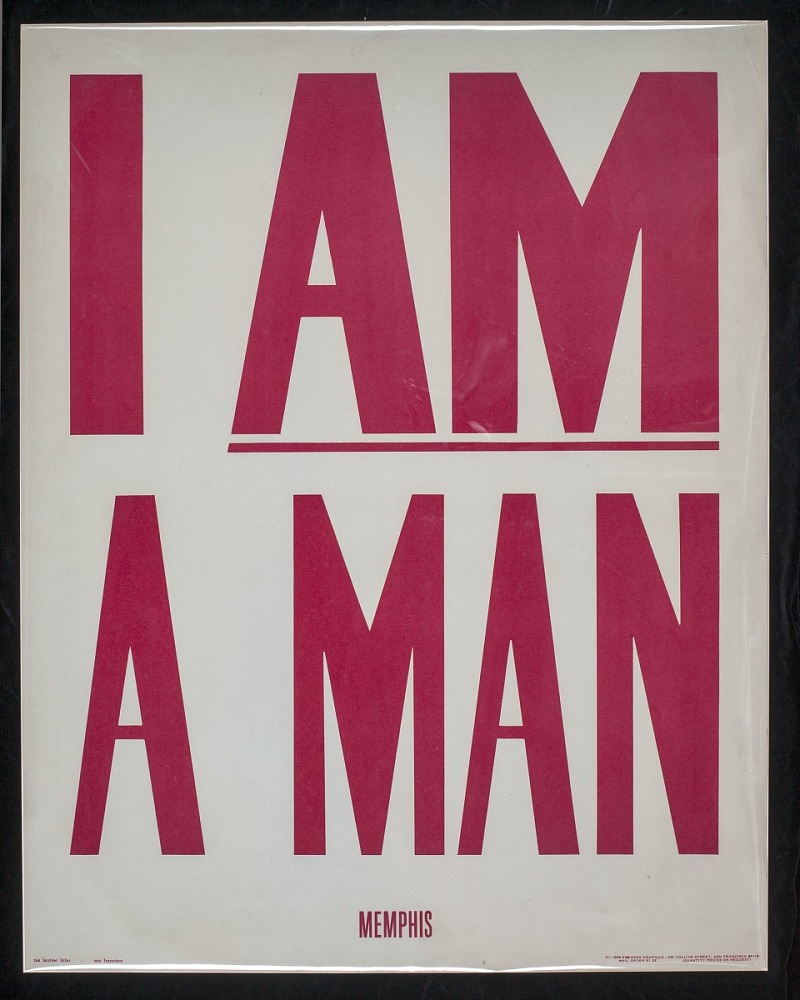

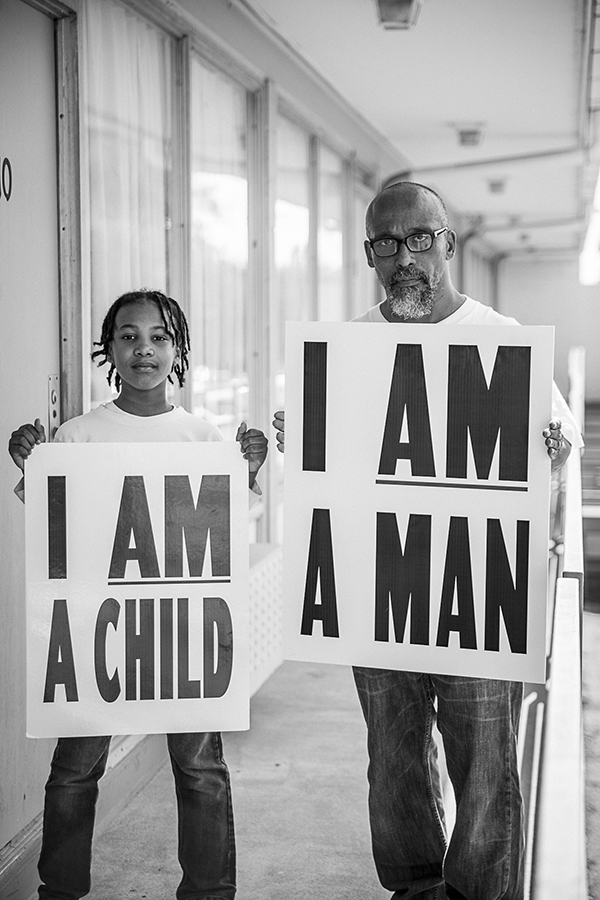

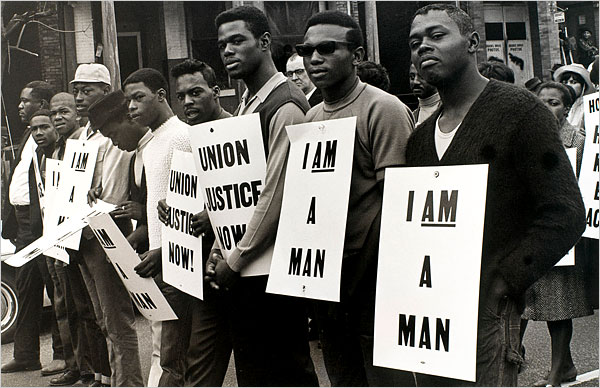

Like the invisible man in Mark 5, black men have consistently been labelled as dangerous, described with language that would render us bestial, animalistic, and beyond the ability to control. Black men have historically been presented as threats – “superpredators” – and are disproportionately impacted by forms of “lethal violence” including murder, incarceration, police brutality, unemployment, and child sexual and physical abuse.

Starting from a young age, black men are talked about as having behavioral challenges that brand them for life “as living terrors” who must be sedated, medicated, or incarcerated in order to be meaningful contributors to the classroom or to society. From the days of chattel slavery black men have been stigmatized and projected on as having “hyperpersonality traits” – traits of hypersexuality and hypermasculinity – which work to rationalize the criminalization and phobias on black male life that play out in black male interactions with police.

According to data from the Washington Post, in 2019 it was reported that 244 black men were killed by police – with 219 in 2018 and 215 in 2017.

The ACLU reports that one in three black boys are expected to go to prison in his lifetime.

A study was recently published that the life expectancy of black men is 71.9 years, far below the life expectancy of white women (81.2), black women (78.5), and white men (76.4). Homicide remains to be the number one cause of death for black males ages 10 to 24. Black men have some of the highest rates of mental health struggles like anxiety and depression. And contrary to popular sentiment, education and wealth are not enough to liberate black men and black boys from suffering under the structural effects of racism and a white male patriarchal society.

For generations black men have been forced to live life among the tombs, and yelling and crying out from the mountaintop for people to free us from our oppression. Yet, as it is for any human being, the longer someone is forced to live among the tombs, the more it begins to take a toll on your flesh and throw dirt on your spirit.

Said differently, the longer anyone is forced to live among the tombs, the more they are being affected by systemic realities that have them trapped and chained. Likewise, the more their cries for help from the mountain top go ignored, the more the body is affected by injustice, then the more the spirit gets infected by grief, despair, rage, and ultimately desperation until you get to a point when you can no longer be subdued, you can no longer be placated, and will struggle and fight by any means necessary to free yourself from the bondages and chains that are keeping you trapped among the tombs.

In his book The Spirituals & the Blues, the late theologian James Cone writes about the realities of black resistance in the antebellum United States, and remarks that when slaves were unable to resist slavery by escaping North to freedom they would find other means to resist such as “shirking their duties, injuring the crops, feigning illness” and being disruptive to the everyday routine. Yet, Cone makes another point that one way black people would practice resistance was by cutting off fingers or injuring a limb as a deliberate act to assert their humanity and to “unfit themselves to work” in an economy and social structure built on the bedrock of their subjugation (pp. 25).

This is why the Bible says that “all day and all night” the unnamed man would cry out and yell from the mountain because he was hoping and praying that somebody, somewhere, would hear his pleas for escape. Thus, he would also cut himself with stones (a euphemism for self mutilation by circumcision) because the more he went unseen, the more his pleas went unheard, then the more he was inclined to turn pain in on himself as a last ditch effort to resist his invisibility.

I am going to pause here parenthetically because I know there are people, today, who know what it’s like to be resorted to turn pain in on yourself. Whether you are black, brown, white, cis, trans, gay, straight, rich or poor, there are people, today, who know what it’s feels like to be invisible, and what it feels like to be silenced and shamed.

There are some people who know the grief, despair, rage, and desperation of living life among the tombs. You are living in the ruins of wrecked relationships. You are living in the tombs of past mistakes. You have watched people die. You have felt yourself trapped with no perceivable way of escape.

Day and night you have cried out from the pain and no one seems to notice or to care, but I want to encourage you to know that wherever you may find yourself in life that this is not the end of your story. Like the unnamed man in our text, you are not destined to live your life among the tombs.

This is not the end of the invisible man’s story because he has an encounter with Jesus at the beginning of his story that sets the trajectory for the end of his story. The invisible man was not meant to remain invisible because he has an encounter with Jesus where three things happen.

First, Jesus sees the man who had otherwise been invisible. Jesus sees him because unlike the others who encountered the man and only saw his surroundings or figments of their imagination, Jesus saw the man and saw the systemic issues that has trapped him and chained him to live his life among the tombs.

Jesus sees the man and does not see a pathological issue projected onto the man. Jesus sees the man and does not see the behavioral issues that are typecast against the man. Jesus sees the man and does not see a spiritual issue that have purportedly cursed and condemned the man. But, Jesus sees the man because has compassion for the man, and understands that there are forces of principalities, powers, and people – rulers, authorities, legislative policies, powers of darkness and forces of spiritual wickedness in heavenly and in earthly places that have conspired to make this man racially and socially invisible.

Second, Jesus hears the man because as the Bible says, after the man sees and approaches Jesus, he falls down and worships Jesus and shouts at the top of his voice, “’What do you want with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God? In God’s name don’t torture me!’”

I am going to stay here for a second because it says much that the man would respond to Jesus in this way. What does it say about religion that when people attempt to approach Jesus they are fearful they will be tormented?

This man had likely been tormented and tortured for so long by the world that he was desperate for Jesus not to treat him the same way. What a terrible and sad day it is when Jesus becomes weaponized against those who are made to live their lives among the tombs. And the man asks Jesus, what do you want with me? because he had spent much of his life being neglected and abused that he surely believed the Son of the Most High God would treat him the same way.

Jesus hears the man and hears the anguish and the despair that has dirtied the man’s spirit. But, Jesus does something that nobody else had bothered to do. Jesus asked the man’s name, and the man answered: “My Name is Legion for we are many,” and when Jesus hears the man’s name Jesus hears that this man embodies “legions” of other invisible “men” – the over 10 million people who are without housing or on the brink of homelessness, the 38.5 million children under 18 who are poor or low income, the 27.5 million people who are without health care protection against COVID 19.

He embodies the legions of black bodies who have been victims of systemic racism and have gone relatively unnamed, unseen, and unheard. He embodies the legions of women, children, queer and transgender youth. Jesus hears the man and hears the stories of the many forced to live life among the tombs.

Finally, Jesus restores the man by clothing the man, setting him back in his right mind, telling the man to return to his people, and cleansing his spirit.

Jesus is moved to act for the liberation of the man because when a person does not have to worry about where their next meal is coming from, having some clothes on their back, free from the bondage of dehumanization and indignity– you will be surprised at how clean somebody’s spirit will become.

Jesus restores the man because Jesus knows that this man’s well being is tied up in respect and acknowledgement of his humanity.

Jesus restores the man because Jesus shows himself to be a friend to the man because as the old saints sing,

What a friend we have in Jesus

All our sins and grieves to bear

What a privilege to carry

Everything to God in prayer

Oh what peace we often forfeit

Of what needless pain we bear

All because we do not carry

Everything to God in prayer

Have we trials and temptation

Is there trouble anywhere

We should never be discouraged

Take it to the Lord in prayer

Oh what peace we often forfeit

Of what needless pain we bear

All because we do not carry

Everything to God in prayer

Let us, like the unnamed man in our text, take everything to God in prayer because God sees us, God hears us, and God is faithful to restore and liberate us from bondage and pains brought on from living life among the tombs.

What Christian America will soon learn is that the man from the tombs was never alone, as much as society wanted him to believe that. Now is the time when others living in the wastes, the queers and the damned, must leave the relative safety of their tombs and bind their fate to the unnamed man publicly (for we know their fates are already inextricably woven together). Once together, our voices will join into one beautiful, powerful harmony, and we shall utter that simple, devastating statement: We are Legion.

LikeLike